|

New and groundbreaking research by scientists at the University of Iceland sheds completely new light on the 1,100-year impact of cod fishing

University of Iceland Research Sheds Light on a 1,100-Year History of Cod Fishing

ICELAND

ICELAND

Monday, February 10, 2025, 04:00 (GMT + 9)

New groundbreaking research by scientists from the University of Iceland has revealed the profound impact of 1,100 years of cod fishing on Iceland's cod population.

According to the study, published in Science Advances, cod during the 10th to 12th centuries were on average 25% larger and lived up to three times longer than today's cod. Despite their impressive size, these cod grew much more slowly, likely due to competition for food within their dense population. According to the study, published in Science Advances, cod during the 10th to 12th centuries were on average 25% larger and lived up to three times longer than today's cod. Despite their impressive size, these cod grew much more slowly, likely due to competition for food within their dense population.

The research team, led by Steven Campana, professor of marine biology at the University of Iceland, included key contributors such as Guðbjörg Ásta Ólafsdóttir, director of the University of Iceland Research Center in Bolungarvík, archaeologist Ragnar Edvardsson, historian Árni Daníel Júlíusson, and Einar Hjörleifsson from the Marine Research Institute.

Early Evidence of Fishing Impacts

The study shows that fishing significantly influenced cod populations as early as the 14th century. "It was surprising to see changes in the cod stock begin so early," noted Guðbjörg Ásta Ólafsdóttir. "This coincided with rising demand for cod in European markets, leading to increased mortality rates in the population." The study shows that fishing significantly influenced cod populations as early as the 14th century. "It was surprising to see changes in the cod stock begin so early," noted Guðbjörg Ásta Ólafsdóttir. "This coincided with rising demand for cod in European markets, leading to increased mortality rates in the population."

The researchers found that before fishing pressure intensified, natural mortality was low, allowing many cod to reach old age. This discovery is essential for understanding historical population dynamics and provides valuable data for modern stock assessments.

Unlocking the Past Through Cod Millstones

A key component of the research involved analyzing ancient cod millstones (otoliths) recovered from archaeological sites. These structures, located in the inner ear of bony fish, store growth rings much like tree trunks. "Millstones act as memory blocks of a fish’s life," explained Steven Campana. "By analyzing them, we can reconstruct the growth, age, and environmental conditions cod experienced over the centuries." A key component of the research involved analyzing ancient cod millstones (otoliths) recovered from archaeological sites. These structures, located in the inner ear of bony fish, store growth rings much like tree trunks. "Millstones act as memory blocks of a fish’s life," explained Steven Campana. "By analyzing them, we can reconstruct the growth, age, and environmental conditions cod experienced over the centuries."

This innovative approach provided a detailed timeline of cod population changes from the early settlement era to the present.

Historical and Archaeological Collaboration

The research has roots in archaeological studies led by Ragnar Edvardsson, whose work on ancient fishing sites in Skálavík and Breiðuvík highlighted the importance of cod fishing to Icelandic society. "The development of Icelandic society has always been closely linked to the cod stock," said Edvardsson.

Historian Árni Daníel Júlíusson contributed valuable historical analyses, estimating Iceland's cod consumption and assessing foreign fishing activities. His findings suggest that European fishing off Iceland may have been much greater than previously assumed, particularly after 1400. Historian Árni Daníel Júlíusson contributed valuable historical analyses, estimating Iceland's cod consumption and assessing foreign fishing activities. His findings suggest that European fishing off Iceland may have been much greater than previously assumed, particularly after 1400.

Key Findings

- Changes in Size and Age: Cod from the 10th to 12th centuries were on average 25% larger and lived up to three times longer than modern cod.

- Fishing Impact: Evidence of fishing's impact emerged as early as the 14th century, coinciding with increased European demand for cod.

- Growth Rates: Ancient cod grew 22% more slowly than modern counterparts, likely due to greater population density.

- Mortality: The study provided rare insights into natural mortality rates, which increased as fishing intensified.

- Fishing Pressure: Findings indicate that European fishing in earlier centuries was more extensive than previously believed.

- Environmental Impact: Despite climate fluctuations, the study underscores fishing pressure as the primary driver of long-term population changes.

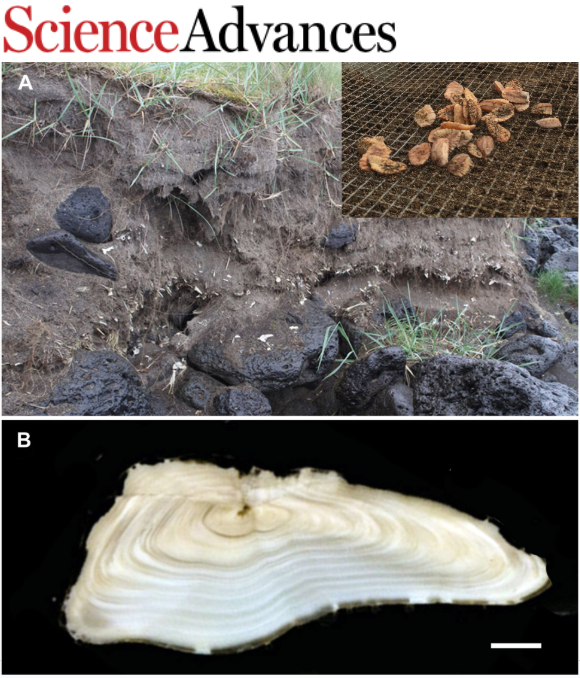

Otolith sampling and quality

(A) Sampling site in Gufuskálar showing fish bones and otoliths in situ. Image credit: F.J.F., City University of New York. Insert shows 15th century cod otoliths from the Breiðavik site. Image credit: G.A.O., University of Iceland. (B) Annual growth bands visible in a transverse section of an 11-year-old cod otolith from the 15th century. Only those sections where the diameter was intact and annual growth increments were visible were used for fish length and age estimation. Scale bar, 1 mm. Image credit: S.E.C., University of Iceland.

A Collaborative Effort

The research combined expertise across disciplines, from marine biology and archaeology to history and fisheries science. It was largely funded by an NSF grant led by George Hambrecht (University of Maryland) and Nicole Misarti (University of Alaska), with ongoing contributions from doctoral students conducting chemical and ecological analyses.

Steven Campana summarized the findings: "If quotas had been in place during the settlement era, they would have been three times larger than today, with fish much easier to catch. This study not only offers a window into the past but also provides critical insights for sustainable fisheries management today."

[email protected]

www.seafood.media

|